This week our guest blogger, Tom Oberst of the University of Exeter, takes us through what the ancient sources reveal about the mysterious and violent cult of the ‘King of the Grove’ at Nemi.

The temple beside the SpeculumDianae is one of the more conspicuous, tangible aspects of the history of the area. Yet, as so often is the case, it was the mysterious side that garnered so much interest in the late 19th Century. Sir James George Frazer wrote a monumental tome attempting to use these more mystical aspects to channel his universalist ideas about the progression of understanding from sympathetic magic via religion to science. His work was named The Golden Bough, a reference to a notorious cult, allegedly situated in the woods surrounding the temple in which the herm of Fundilia resided.

The Golden Bough by J. M. W. Turner, inspired by Vergil’s Aeneid. Photo: Tate

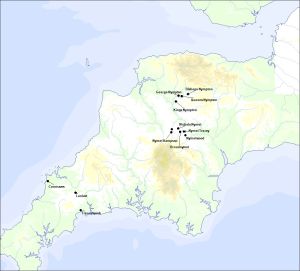

This cult, now know as the cult of the rex nemorensis (lit. king of the grove), has not left any archaeological evidence of its existence except, arguably, the double headed herm, found in the Nottingham Castle Museum. The only real evidence we have for this cult are the numerous references in ancient literature. The archaeological data makes it quite clear that the temple was relatively popular, yet in literature the key words are the nemus or lucus (grove), usually described as sacred to Diana, but always located on the banks of Lake Nemi or near the ancient town of Aricia, modern day Ariccia. What this tells us is that there was something significant about the Arician grove, something that made Roman and Greek authors reference it in their prose and poetry, or use it as a topographical marker. Lake Nemi was clearly an important spot, Caligula relaxed on his floating palaces there, and Caesar had a mansion overlooking it (Suet. DivJul. 46), yet it consistently seems to be the surrounding woods that fascinate. I have complied a list of references I have come across to the grove or the cult of the rex nemorensis in my research on its thematic appearance in Latin epic poetry. There are surely more, unfortunately I have yet to come across them.

So what was this cult? Carin Green’s 2007 book, Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, dedicates a whole chapter to this discussion which is excellent and well worth a read for a more in depth analysis of the sources (although I feel she is a little too liberal with her analysis of the literary data). There was a small group which lived in the woods surrounding Lake Nemi who were ruled by a priest king, the rex nemorensis. Strabo (5.3.12) tells us that the priest had to be a fugitive, which has led many to assume that the majority, if not all, of the inhabitants of the grove were also fugitives. We know nothing about their lifestyle, whether they lived in the grove, or used it for purely ritualistic purposes. What we do know about is the rex.

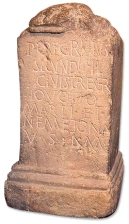

Double headed herm possibly depicting the Rex Nemorensis. ©Nottingham City Museums & Galleries. Photo: author’s own

The rex was part of a perpetual tragedy in which successor became succeeded in a bloody fight to the death. Sources differ about the nature of the rite but there they all agree that at some point, the rex carried a sword with him, and could be challenged by a fugitive for kingship of the grove. Servius, in his Fourth Century commentary on Vergil’s Aeneid, mentions the significance of a bough, a branch which had to be broken off in order to commence the challenge (A. 6.136). Despite the fact that Servius is our only source about the bough in this context it is one of the most well known features of this rite, thanks to Frazer and his dubious assertion that this bough is Vergil’s aureus, the ‘Golden Bough’ (6.136). Frazer’s reasoning is dubious because he claims that the aureas is the bough of the Arician cult, whereas Servius claims that it is merely an allusion. This blasé interpretation of sources is something one becomes accustomed to after reading a few pages of The Golden Bough. Ancient authors who are often overlooked are Ovid (Ars. 1.259-62; Fast. 3. 269-72), Pausanias (27.4), Servius (A. 6.136), Strabo (5.3.12), Suetonius (Cal. 35. 3) and Valerius Flaccus (2.300-5) who all mention a king, usually a priest to Diana, who wanders around the Arician grove carrying a sword, and explain that his successor was chosen through a murderous or sacrificial duel. Unfortunately they do not elaborate on how this duel was fought.

A second important extratextual clue our literary sources can give us is the dates in which they were written, or were written about. Our sources range from the 1st Century B.C. to the 4th A.D., which, although this is not conclusive proof of its actual longevity, does display the extent of its fame.

So there you have it! A brief outline of the elusive rex. There is a lot of conjecture out there about the rite’s practices, symbolism and participants, and I would advise erring on the side of sceptical if you go on to read the suggested ‘further reading’ (below), but I do hope I’ve whetted your appetite about one of the more fascinating characters of ancient Italy.

Suggested reading:

Alfoldi, A. (1960) ‘Diana Nemorensis’, AJA 64: 137-144.

Dyson, J (2001) King of the Wood: The Sacrificial Victor in Vergil’s Aeneid, Oklahoma.

Frazer, J. G. (1890) The Golden Bough, abr. Fraser, R. (1994) Oxford.

Green, C. M. C. (1994) ‘The Necessary Murder: Myth, Ritual, and Civil War in Lucan, Book 3’, CA 13: 203-33.

Green, C. M. C. (2006) Roman Religion and the Cult of Diana at Aricia, Cambridge.

MacCormick, A. G. & Blagg, F. C. eds. (1983) Mysteries of Diana: The Antiquities from Nemi in Nottingham Museums, Nottingham.