Diana

The goddess Diana was the Roman counterpart of the Greek goddess Artemis. She was best known as the goddess of the hunt, nature and animals. Later, she also became known as goddess of the moon. She was the daughter of Jupiter (king of the gods) and Latona, and was the twin sister of Apollo (god of the sun).

In most depictions she is shown carrying a bow and arrows while wearing a small crescent moon in her hair. Her most sacred animals were deer, bears and hunting dogs. Diana was also the goddess of birth, even though she herself remained a virgin. Both animals and humans were protected by her and their fertility was Diana’s concern.

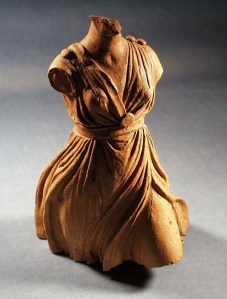

In trying to appease the goddess, young men and women offered the goddess votives to secure healthy and strong offspring. Amongst these votives could be various jewellery objects, statuettes and figurines either of the goddess or her devotees and figurines of animals. Votives offered to Diana quite often show a very strong connection with nature in all its manifestations, relating to her nature as goddess of the hunt and fertility. This can be illustrated by looking at the votive offerings found on site, which include human body parts like the uterus.

Diana Nemorensis

Diana was known in different characters. One of her guises was Diana Nemorensis (Diana of Nemi). The sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis was found on the northern shore of Lake Nemi and her cult was particularly violent. The Romans frequently adopted Greek divinities and merged them with their own, which resulted in several legends that refer to the origin of the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis.

One of the legends goes that there was a large oak tree to be found in her sacred grove at Nemi. It was absolutely forbidden to break off any of its branches (some say the mistletoe surrounding it). The only people allowed to do so were fugitive slaves. Breaking off one of the branches gave the slaves the right to fight the presiding high priest of the temple to the death. If the challenger won, he could take the place, adopting the title of rex nemorensis, king of the sacred grove.

Denarius (Roman coin) of Diana and triple cult statue of Diana Nemorensis on reverse, minted 43 BC. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The tale of the rex nemorensis is told in the ancient sources. Ovid’s description (Fasti Book 3) reads:

‘one with strong hands and swift feet rules there, and each is later killed, as he himself killed before’.

According to the British anthropologist Sir James Frazer, the rule of the sanctuary was that:

‘A candidate for the priesthood could only succeed to office by slaying the priest, and having slain him, he retained office till he himself was slain by a stronger or a craftier.’

Origins of the Legend

This bloody ritual could be explained as a variation on the story of Orestes, known in Greek mythology. Orestes (son of the king and queen of Mycenae, Agamemnon and Clytemnestra) killed his mother and her lover to avenge his father. To purify himself the god Apollo sent him to Tauris. Iphegeneia, Orestes’ sister was the priestess of the local divinity, Artemis of Tauris. The cult of Artemis of Tauris was known for killing all the foreigners that came to shore.

After tricking the king of the Tauric Chersonese to escape an unfortunate ending, Orestes fled with his sister to Italy. They took the image of the Tauric Artemis with them and the cult of Artemis of Tauris took hold in the woods of Nemi. This barbaric goddess was known for the bloody rituals taking place in her sanctuaries; every stranger who landed on the shore was sacrificed on her altar.

The ritual in Nemi can be interpreted as a milder form of this gruesome practice. However, the goddess still could only be appeased properly with human blood. The death of the rex nemorensis or his challenger had to be violent, ‘as the spurting blood from the loser was meant to fertilise the surrounding ground’, as Ludovico Pisani argues.

Another tradition, again of Greek origin, explains the existence of the first rex nemorensis. According to the Aricians, the priesthood would have been held by Hippolytus. Hippolytus, after being unjustly killed by his father, was resurrected by Asclepius (the god of healing, Aesculapius in Latin) with the aid of Artemis. He was named Virbius (twice man) and went on to become a king, devoting a place of worship to Artemis. Diana was also called Virbia, which helps to explain the connection between her perceived healing powers and those of Virbius, who became a minor deity himself.

Celebrating Diana at Nemi

Diana was honoured at Nemi by an annual festival on August 13th (which, incidentally, is also our Twitter guru Fundilia’s birthday!) called Nemoralia. Burning torches were carried in a procession around the lake, known as Speculum Dianae (Diana’s Mirror). Those whose prayers had been answered would attend wearing wreaths of flowers, in order to fulfil vows made to the goddess. Hounds were honoured out of respect for Diana’s role as the goddess of the hunt. The day is also known as servorum dies festus, as it was holiday for slaves.

Ruth Léger, researcher, University of Birmingham

Don’t forget, ‘Romans’ FREE event on 5th August 2013 when standard admissions tickets are bought http://www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/index.aspx?articleid=5569&eventId=5868

![NCM 1890-1357-8 Anatomical etc. votive offerings [ii]](https://nemitonottingham.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/ncm-1890-1357-8-anatomical-etc-votive-offerings-ii.jpg?w=150&h=103)