We are delighted to announce today’s blog is hosted by Ann Inscker, curator of The Treasures of Nemi exhibition. Here she reflects on her busy and challenging week preparing the museum space and displays for the exhibition’s launch, which took place last Friday, 19th July 2013.

Monday 15th July

Work was already in full swing, the galleries were painted, the majority of the objects had been brought up the hill from the Brewhouse Yard site and the plinths, altars and display shelving etc. were all being painted appropriate colours for the rooms into which they would eventually sit. The remarkable team of technicians, who I had not worked with previously, were all diligently going about their work with little fuss, under the supervision of the Design Technician, the Assistant Conservator and the Exhibition Officer, a very impressive site. I was accompanied by my two foreign placement students, Nicole from Australia and Sophie from Canada, on a museum and heritage programme from their respective home countries with Bishop Grosseteste University in Lincoln. They were my much needed extra pairs of hands, to make up for my current state being heavily pregnant with twins.

A couple of minutes after we arrived, Andrew from the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, arrived with a wonderful watercolour and chalk drawing, “The Lake of Nemi and the town of Genzano’ by John Robert Cozens which was duly hung on the wall while he observed. This, the first object to be installed, is remarkable and although painted in the eighteenth century still reflects some of the mystic charm and serene beauty you might have observed in ancient times and which still lingers when you visit the lake today. Following Andrew’s departure our other loan items, a marble bust of Lord Savile, the excavator of our Nemi collection, arrived from Leeds Museums and a voluptuous painting of Diana, attributed to Antonio Bellucci {1716-22] from Northampton Museums. Sadly for my placement students the bust remained in it’s box awaiting a plinth from the workshop in the bowels of the Castle Museum and the painting was turned face down so that an assessment could be made for the fixings.

Thus we turned our attention to placing masking tape where some of the plinths and objects were to be located around the three galleries and moved a few of the completed items into place, where possible.

Tuesday 16th July

Sophie and Nicole carried on working on their educational activity sheets for the gallery, while I ploughed on with other work of a classical nature, at my lap top in the gallery, until I was needed to give direction. Ian our labels and vinyl man arrived with the labels and a number of text panels and promises of a return visit on Friday to do the floor and wall vinyl and the technicians, having painted all the plinths several times, began arranging the wall shelving supports for the Etruscan and Roman building material displays.

Sophie and Nicole carried on working on their educational activity sheets for the gallery, while I ploughed on with other work of a classical nature, at my lap top in the gallery, until I was needed to give direction. Ian our labels and vinyl man arrived with the labels and a number of text panels and promises of a return visit on Friday to do the floor and wall vinyl and the technicians, having painted all the plinths several times, began arranging the wall shelving supports for the Etruscan and Roman building material displays.

We helped locate some of the plinths appropriately and watched with trepidation as Fundilia was put back together. A fracture along her left shoulder, established as result of the expanding iron inserts which would have originally held her arms on both sides, had previously expanded, resulting in a breakage once she was lifted in the stores to make her way up to the Castle. Fortunately, all was salvageable and the Assistant Conservator glued the two broken elements back together and left them over night to set. The red paint in the end gallery in which she will sit, provides a heightened sense of drama and sets off the marble sculptures beautifully.

Wednesday 17th July

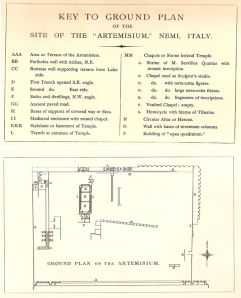

Work began on the altar layouts, starting with the Cica. Pre 200 BC layout. This case contains the largest number of objects at around 70 and so was a big challenge, though thoroughly needed to put across the cramped nature of Etruscan altars and to show the rich variety of figurines deposited, one of the unique features of the finds from Nemi. Another of my volunteers, John, joined me in the afternoon to take photographs of the installation.

The bust of Lord Savile by Van der Kerkhove Saibas, kindly loaned by Leeds Museums, was finally lifted on to a newly painted plinth by the team, his head subtly turned to observe visitors making their way in to the second gallery. Savile fittingly sits next to the superb Cozens watercolour. Leeds will be doing an exhibition on Savile in 2014 and are likely to request a number of items from this collection to join the material they hold from the Lanuvium villa of the emperor Antoninus Pius which Savile excavated prior to Nemi.

We laid out the banners representing the missing sculptures from the Fundilia Room, in the wall niches at the back of the sanctuary, leaving our sole representative, the Fundilia herm, as the star attraction. The other sculptures are at the Ny Carlesberg in Copenhagen and sadly floor loading and expense, prevented us from requesting the originals. Instead photographs of the portrait busts were printed on fabric, located in their correct positions and expertly hung by Design Technician Russell, using Boaden cable, named after Sir Frank Boaden, founder of Raleigh bicycles here in Nottingham and made from the same material for break cables no less!

Thursday 18th July [The Longest Day]

Having set up my Industrial volunteers down at Brewhouse and printed off the educational sheets worked on by placement students Nicole and Sophie, Nicole joined me in coming up to the Castle. Today was going to be very exciting, as the massive oak tree, representing the ‘Golden Bough’ of the Rex Nemorensis, or King of the Woods, was arriving. When we got up the hill the magnificent tree had already arrived and was looking fabulous against the red background walls. In the afternoon, I Christened, or should I say ‘Votived’ the tree, by being the first to follow Ovid’s description of messages in the trees around the sanctuary, by hanging my personal message in the tree. As I am pregnant, it seemed apt to ask for the safe delivery of my twins.

The first job after tree inspection, was to check and locate the reproduction images taken from Savile’s sepia photographs and those taken by myself and my husband, Mark, during our visit to the site in 2010. Unfortunately, a mini panic attack occurred when I realised 10 important images were missing. We rushed to the Exhibitions Team Office where Tris, the Exhibitions Officer, put through an urgent order with no guarantee that the items would turn up until the afternoon. Fingers were crossed and they turned up in the afternoon and were duly laid out in their appropriate locations.

We then commenced numbering the Pre and Post 200 BC altars, laid out and subsequently numbered the four pillar display cases [gaming, bone and glass, bronze and finally coinage] and lastly numbered the two architectural displays. Although this may not sound like a huge amount of work, all the checking against the layout plans and text, meant that neither myself, or poor Nicole, left the Castle until almost 7.30pm. As I had started at 7.30am, this was a long day and it wasn’t over yet. I had 17 applications for my maternity cover to look through once I got home, happy days.

The technicians had again proved themselves, setting up Asclepious, the herm of Lucius Faenius Faustus, possibly the oldest dedication to the lowliest of actors known and the majority of the architectural objects. The latter, being displayed at height, for the first time to my knowledge, and with a white, rather than yellow light, all look remarkable on the wall.

Friday 19th July [opening day and still a lot to do]

Earlier start today, again having set up my Industrial volunteers back at Brewhouse beforehand. I came up to the castle armed with the educational sheets and a number of site images checked against their formal names, giving me the chance to alter the arrangement of some of the site images before they went up. Today the floor and inscription wall vinyl arrives, along with the Byron material from Newstead Abbey [Childe Harrold’s Pilgrimage Forth Canto] and a number of Diana related items from Fine and Decorative Art, including a painting of Diana after Titian. The latter, based on a naked Venus draped across a bed, had recently returned from conservation work to the frame and cleaning. It would appear, the already sexy Diana was even sexier following her cleaning, as her arm had been over-painted to cover some of her modesty at a later date.

The team again worked perfectly and very calmly together, right up to the line, putting up the last of the text panels, the framed works, cabinet lids, labels, arranging the lighting and cleaning through the galleries and removing kit. Ian the vinyl specialist arrived to install the Via Verbia or ‘sacred way’ in the first gallery, the wall inscription of Diana’s attributes and the mosaic floor inscription in the Fundilia Room, all helping to set the scene. The galleries were finally completed at 6pm, just in time for the arrival of the public for the private view.

Having made a swift change, I arrived back at the castle in time to meet Associate Professor of Classics at Nottingham University, Katharina Lorenz, who would be opening the exhibition. I escorted her through the galleries, before taking her to the café to participate in the speeches. The turn out was very good with a number of familiar faces to the archaeological collections in attendance, including Mark Patterson who would be providing one of the lectures to accompany the exhibition and was there in his freelance reporter capacity, to write a critique of the exhibition for the ‘Nottingham Evening Post.’ On Monday Victoria Donnellan will come to do the same for ‘The Museums Journal.’

The exhibition was well received from all who came to speak to me and I was delighted to see the wonderful oak tree already carrying a number of votive messages. With my pregnant legs having swelled somewhat, I went home exhausted but elated that we had met the deadline. Only three more events to get through over the next two weeks, then I can pass the baton on to my maternity cover, whoever they may be.

Ann Inscker, curator at Nottingham City Museums and Galleries and the Treasures of Nemi: Finds from the Sanctuary of Diana exhibition.